Inside the Studio: Tommy Simpson on composing film scores with Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross

Samuel Taggart

10 Minutes

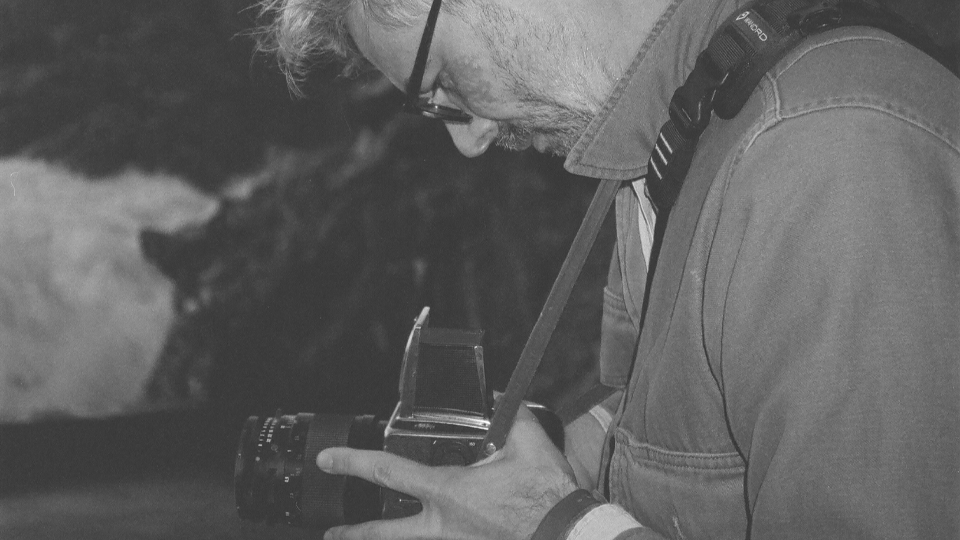

Music has a way of shaping our lives in unexpected ways. For Tommy Simpson, though, it's everything. From his earliest memories taking piano lessons, writing Nintendo-inspired ditties on the keyboard, and just messing around in GarageBand, to finding his stride crafting soundscapes & scores for feature films, as well as making his own music under the moniker Macro/micro, Simpson’s journey is a testament to how personal curiosity, creative discipline, and passion can lead one down fulfilling & exciting paths.

In this conversation, the Los Angeles-based composer, sound designer, audio engineer, and electronic music artist reflects on the pivotal moments that have shaped his career. From mastering modular synthesizers to navigating the high-pressure demands of studio work alongside industry legends Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross, Simpson's path highlights the importance of taking chances, making personal connections, and nurturing a creative process that’s as technical as it is exploratory.

Whether you're a budding musician, a tenured engineer, or simply curious to learn more about the craft behind movie scores, Simpson's insights here illuminate the magic of turning sound into story and offer valuable for advice for any creative trying to turn their dreams into reality.

What drew you into music? How did it evolve into your full-time path?

I had a lot of musical imprinting early on. The first instrument I played was the piano—my parents gave me lessons when I was around five-years-old. I would make up little ditties, like I'd be playing Super Nintendo then I’d try to make evil sounding Bowser music on the piano. [Laughs] Those are some of my earliest memories of making music.

It got more serious, and in my teenage years guitar became my big thing. That’s when I discovered GarageBand on the computer, and started writing & recording songs probably around 13-years-old. I got more and more into synthesizers and went back to playing the keyboard. I've always appreciated the cutting-edge of production. Back then, I was just a teenager falling in love with Nine Inch Nails and Radiohead as prime examples of bands that completely pushed all production limits. From there, I started focusing more on the recording side, switching from GarageBand to Logic to Ableton, which is such a creative tool on its own. It's really its own instrument, especially how you can route audio through different channels and effects. Now I just say “I play the computer.” [Laughs]

You’ve been credited as a Composer, Score Engineer, and Sound Designer… can you explain the difference between these roles?

When you hear what we call “needle drops,” when someone is picking music you’ve heard before, that’s the job a Music Supervisor, who manages the sourcing, pitching, acquiring the rights of pre-existing music. You hear it all the time in Quentin Tarantino movies.

The Composer, on the other hand, creates all the original music for the movie. A Score Engineer helps the composer in the studio while they're creating the score, basically assisting in any kind of studio-related tasks related to recording. When I was working for Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, they didn’t need a lot of help because they're f*cking wizards, pardon my French. Every now and then, though, they’d ask me to turn a knob with a free hand or set up synths in a particular way. Trent would ask to have a specific instrument patched through a certain pedal… and it was always, “Could you please do this as quick as possible because I want to play it right now?” [Laughs] So, as that assistant, you're running, grabbing all of the gear, plugging it in, getting it into a nice ergonomic, performable setup…

Sound Design, lastly, is something closer to composing. You're creating original audio, but it's more like sound effects, or a way of emphasizing certain actions you're seeing on-screen with a dramatized sound.

What's your typical process when approaching a new project?

Different people have different approaches. There's plenty of folks who, when they write music, are more like Michelangelo; they approach it like “David's inside the marble, and I'm just going to chip away the parts that aren't David.” There are also composers who already have a preconceived notion of what they're trying to make.

For me, especially with the work I’m doing for Macro/micro, I don't come with any thoughts or preconceived notions. I try to bring myself, and all the feelings and emotions that are bouncing around in my heart and my mind, and let those things guide me while I play with sound. I always want to experiment, so while I have an orientation in myself of my interests and feelings, I don't come with a specific goal. If something catches my ear, I’ll go down that rabbit hoIe. This process informs me and evolves. Only once I have a solid idea, that’s when I’ll step into editor mode to start sculpting, making adjustments to achieve a specific result. But I try to kick that down the road as far as possible.

In scoring, it's more difficult because the nature of the beast is trying to create specific cues that hit different emotional beats within the film’s roadmap. I often won't even start with it direct-to-picture—I'm first creating sounds in a vacuum. Once I get a few exciting elements, thats’ when I’ll start pulling those sounds into the into the film session and start trying to see how these things can evolve. I always start by staying in the sonic realm.

A huge influence on your life & career has been working alongside the legendary musician/composer duo, Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross. How did you get involved with those two?

They’ve had a touring agent that's been with them forever, and I loosely knew him, having met at various screenings. Normally, I’m a bit shy, but I had just gotten married and I was dreaming big. I was thinking—however unrealistic—the coolest job I could have would be working for Trent and Atticus, so I thought to write to their agent and see if they needed anyone to make coffee, sweep the leaves, or anything at all…

At that point, they were ending their tour for their “Bad Witch” album, and were playing a few shows in LA. Being a huge fan, I also figured they were finishing some scoring project they had started on the road. Reaching out to their agent, I tried to be persistent but not annoying; I didn't get the first email reply, but on the second one he said we should meet up at one of the shows. I think he was just trying to feel me out, make sure I actually knew my stuff. We chatted, but there were no promises given. A couple months later, I got a call from Trent’s then-manager saying they needed someone to run gear from storage to the studio. He asked me when I could start, and I replied, “Right now?!”

It was supposed to only be for like a week or two, just hauling gear. But, one day, I’m bringing some super cool synth into the studio, and I see Trent. I had to make a comment about the synth, which got us talking about gear. From there, it just naturally just progressed into being a general studio assistant, getting lunch, making the coffees; then I took on more studio responsibilities and eventually started working as an Engineer. It all came from reaching out to that personal connection, and bringing an eagerness to do any kind of job at all—there was nothing beneath me. Sure, it helped to show up on time with a good attitude, and to be a like-minded synth dork.

How did these experiences handling equipment & working as a studio assistant help shape your current approach to music & composing?

The one thing that really sticks out is that I just got over my fear of reading the damn manual! [Laughs] Growing up, if it was my own gear, I’d get a synth and I’d figure out what I could; if I couldn't figure out something more technical, I’d just avoid doing it. When you get to work for your musical idol, and he says you need to set something up, you're gonna figure out how to make it work! [Laughs] I was so allergic to manuals, or trying to do anything that was outside of a quick search on YouTube—but Trent’s studio is like a museum of synthesizers. Some are vintage and others were built by an obscure guy in some Eastern European country, and instead of coming with a manual have a little handwritten cheat sheet that you have to decipher on your own. It just really got me so much more comfortable with figuring out how each instrument actually works. Diving deeper in how to use these tools exponentially increased my ability to create, and to figure out more interesting ways of making sounds.

What’s one of the biggest takeaways from those experiences with Trent & Atticus?

The one thing that I really took away from that experience was the professional discipline, how to organize your mind, your time and your work ethic for a project. I learned to treat my creativity like a job, where you show up to work and you stay at it, so at the end of the day you feel like you’ve accomplished something. It’s not about just catching inspiration when the muse comes.

Approaching it this way provides me with more energy and focus to sustain my creativity, too. When you’re only relying on that inspiration to strike, waiting for the winds to blow, you end up shrinking the amount of time that you’re creative overall. Starting to view that creativity as a daily ritual, a practice, it takes away the guesswork, and lets your mind more easily enter that flow state.

Stepping into the studio became a zen-like experience, going through “the practice,” as opposed to chasing some deep psychedelic moment of how to approach a project. This also instills more agency in me, as an individual, to get the damn thing done. I just love being in the studio, making sounds, so the more I do that, the happier I am. It’s a positive feedback loop.

How does research play into the sounds & atmospheres you create for films?

Most every project that I've been involved in has either been contemporary or related to Sci-Fi, so the planning that happens when creating for a “period piece,” for example, isn’t usually on my radar. For me, I get to make the rules and invent the sounds of these future/modern environments…

However, I was tangentially involved with “Mank,” the Citizen Kane movie, while working with Trent and Atticus as a Score Engineer. They wanted to use all period instruments and a period-style score, so I had to listen to big band music, classic scores of Hitchcock movies, and sort out those vibes.

It would be really interesting to have a project, say, set in the Dark Ages in Scotland, and to have to learn how to play the Hurdy Gurdy… but I just haven't had that opportunity yet.

How do find the right instruments & sounds to use for each project?

For me, it's always about finding something cool and unique. For instance, the Teenage Engineering OP1 has this old school Gameboy look to it, but it has so many unique sequencer algorithms and synth engines that make it fun to play with. I could say the same for a bunch of modular stuff on the wall in my studio. It all goes back to just playing with sound, and not thinking too much about how things should sound ahead of time. Those moments of creative sandboxing, playing with the tools, seeing what happens next, playing something in a way I haven’t before and letting that create surprising results—those are some of the most inspiring moments.

The really wonderful thing with a synthesizer, or using samples, is you can make them sound completely different from where you started. There’s this creative snowballing that occurs, which leads me less down a path of playing a specific instrument, and more toward discovering new sounds.

Can you talk about the relationship between technology and tradition in music?

When I started getting into modular synthesizers, I had to learn these different terms that were developed in the 1960s, like what a “gate” meant. At first I was like, “There’s no gate! What is this?!” [Laughs] But I learned that it’s just an electrical signal, a square wave. Essentially, you’re turning a pathway on or off, open or closed. Once I grasped that concept, I could start stringing it together with others, like the “logic” or “patterns” of modular synthesizers.

I've got an old school Moog System 55, which has no easy screens; you just gotta learn your terms. As I learned more about how synthesizers work—all the nuts and bolts—I was able to look at Ableton differently and utilize those same principles. That’s when I started actually understanding the concepts instead of just parroting them back.

What makes certain composers, like Hans Zimmer, so sought-after?

That's a great question. Essentially, yes, he’s a composer, but he's also, in essence, the CEO of a Music Factory at his company, Remote Control Productions. I interned there for a short period of time more than a decade ago, and it was really interesting to see how, with a staff of 80 composers and assistants, they would take on projects left and right. For most projects nowadays, Hans himself will write the theme, and other composers will flesh it out. One of the reasons he’s so successful is that he’s just super effective at communicating the work he’s completed. I never had too much time with him, but whenever we were in the same room, he was just fun to be around, always making little jokes, very gregarious—he was always selling the feeling you wanted from a collaborator.

It comes back to something I learned in college composition courses—we were encouraged to be “outdoor cats,” not introverted, “indoor cats.” This attitude can be really helpful when you’re looking for gigs—just being out there meeting people, networking, you're gonna get a lot more gigs than if you just make great music. All of my best jobs always came from some personal connection. It's rare that something just falls into your lap, or a random cold email gets you the job you’ve been seeking. It’s really about going out, meeting people, doing as much of that networking as you can—that’s where the work will come from.

What are some of your favorite instruments to work with, and why?

I’ll start with outboard synths, some actual, physical synths. I really love the OB6 built by Dave Smith and Tom Oberheim, it’s a polyphonic analog synthesizer that produces really beautiful and rich sounds, and has some great features like this randomized de-tuning knob, so you can control how precisely each note lands on the exact frequency, or if it’s going to drift a little bit. It helps create this the subconscious, almost acoustic kind of feel to it—each time you're hitting a note it doesn’t sound the same, it’s a little different.

I really love all of my modular synthesizer equipment, and there are tons of different companies that make individual, specific parts of a synthesizer—you end up Frankenstein-ing your own synth with one company’s filter and a different company's sequencer, and so on. This is indispensable for me—I just love it. It's that's the most fun I have in the studio. It can seem a bit unwieldy or hard to navigate, but you just treat it like a zen sandbox, always playing with it, pulling cables, warping sounds to get what you want out of it.

The other thing I’ve been really enjoying lately are Ableton’s stock plugins. I’m realizing more and more that that you don't have to buy a huge plugin package to get the right sound—what comes with Ableton is so good. One specific plugin is called Corpus, which is essentially a resonator tool that uses extremely short delays to create sounds that seems like they were actually played on a bodied instrument. But, of course, the best way to use it is to abuse it so hard that it doesn't sound like a resonator anymore, so it just sounds like some insane synthesizer. [Laughs]

Who are some of your other biggest musical inspirations?

I already mentioned Radiohead, but I also love the various offshoots that it spawned, like Johnny Greenwood’s movie scores and Tom York’s solo stuff. In the electronic music space, I love the classic Warp Records groups, like Boards of Canada, Aphex Twin and Autechre. Even some newer artists like Jon Hopkins, Four Tet, and Nils Frahm, are really blending between electronic music and contemporary classical.

In terms of composing, Steve Reich and Philip Glass come to mind, especially Philip Glass’ soundtrack to the film “Koyaanisqatsi”, which just slammed into my brain in a way I wasn’t expecting when I was in my early twenties. It’s a lifelong goal of mine to do a film like that, where you're creating a wall-to-wall score for a visual narrative without characters or dialogue. It’s more like a psychedelic narrative, a visually driven story where music plays constantly.

Let’s end on a fun one… What’s a movie that you would have loved to score? How would you approach it differently than what already exists?

Man, I haven't really thought about this before. That's a fun question. I’m surprising myself with this answer, but maybe’s it’s the original “Alien” movie. To me, that film is just absolute perfection—it's not just a sci-fi movie, it's not just a horror movie, and it’s rooted in incredible scientific thought. The pacing of the movie is also perfect—it’s slow, but not boring—it just slowly brings you into the film. All of the super scary, horrific stuff happening in the film would pair really well with more modern-style production, which could help emphasize that “pit in your stomach feeling.” Now, I’m not saying I’d change anything about the original, I just would have been stoked to work on the film and provide a different style to the score.