Drawing the movies: Hollywood Art Director Carl Sprague on illustrating for Wes Anderson & the importance of color in film

Samuel Taggart

12 Minutes

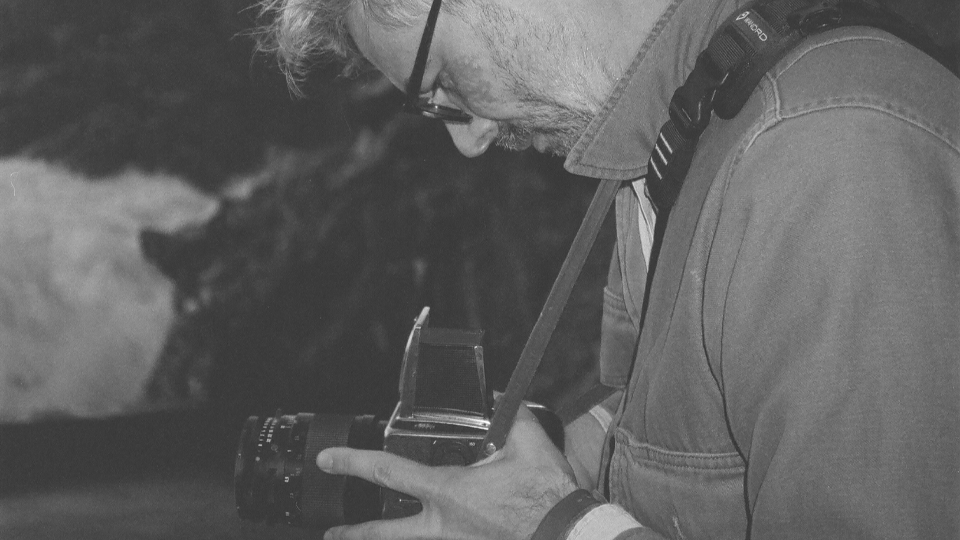

In Carl Sprague’s world, everything begins with a sketch.

The career illustrator has spent the last 30 years working in Art Departments for over 30 films—29 of which have been nominated for Academy Awards, with one, 12 Years A Slave, winning “Best Picture.” Needless to say, Sprague has worked alongside some of the biggest names in the movie business, including Martin Scorsese (The Age Of Innocence), David Fincher (The Social Network), and Steven Spielberg (Amistad)—but his longest-standing collaboration has been with indie film legend Wes Anderson. Operating in various roles, Sprague assisted on The Royal Tenenbaums, Moonrise Kingdom, The Grand Budapest Hotel, and The French Dispatch.

Sprague is the one who, quite literally, helps turn the creative fantasies of filmmakers into realities; whether acting as Art Director composing a film’s palette from a high-level; Concept Illustrator working out the details of a character’s bedroom; or Production Designer turning drawings meant to inspire into blueprints for set design. Using his preferred Mirado Black Warrior #2 pencil, Sprague takes scripts & sketches concepts; those initial drawings go through iterations that can become anything from a period-piece prop to a complete set design.

For instance, Sprague is the one who took a reference photo of a hotel in Austria and translated it into the facade & interior set design for the Grand Budapest Hotel, featured in the synonymous Anderson film from 2104—yes, the image of the hotel featured in every movie poster for the film began as a sketch; then it was actually built with the help of Sprague’s architectural measurements & set-building insights. In the Art Department, there are roles that teeter into the realm of construction & engineering; others that strictly focus on creative pursuits like color & costume. Sprague has done it all for Hollywood movies, television, and advertising.

What began as a childhood fascination with marionette theater—more on this later—has blossomed into a lifetime of pursuing imagination & turning it into real-world designs for cameras to capture. In this exclusive interview, Sprague shares insights from his 30-plus years in Hollywood, speaks about his creative process (that always starts with the script), discusses his current pursuits teaching, and shares his perspective on importance of color in film.

What’s shakin’ in the world of Carl Sprague?

In February, I had a nice moment at the Opalka Gallery. It’s a lovely space that offered me a retrospective show. It’s was delightful, and it made me realize, “Oh my gosh, you just keep on putting one foot in front of the other and suddenly you’ve done so much!” I have drawers bursting with drawings. It's nice to share them.

Apart from the retrospective, what else are you working on?

Later today, I plan to read a few scripts that a group in London sent me about an animation project. I also took a job teaching at Boston University, so that's fun. I'm going there tomorrow; I have 15 kids in my class and they're interested in Production Design. It's fun to brush up against youth—they're young, they're fresh, and they're remarkably uninformed, so it doesn't make it that hard for me to fill up a couple hours of classroom time. [Laughs]

Have you ever taught before?

I've done a lot of lecturing, but to teach something as nebulous as production design... I studied a bit in theatrical design and learning how to draw and to draft, which is, can I say… more “contained.” In the theater, each person [in the audience] has a seat and there's roughly one angle they’ll use to view the stage, and the room is only so big.

Film is all over the map; the viewer’s perspective can be from anywhere. With editing, CGI, visual effects, and animation, it's a blank slate. It's new trying to teach this discipline. I'm trying to focus on demystifying the pencil for these 20-year-olds. Every class I’ll say: “Here's a pencil. Here's a piece of paper. Here's something to draw.” We’ll do that for at least half-an-hour every time—try to instill the idea that the pencil is your friend.

How does your role as an Illustrator/Art Director fit into the bigger production?

It's all part of an incremental process: You start with words then make images… and try to figure out, “What are we actually going to do [when we build it]?” For the set on the Grand Budapest, there was a lovely storyboard showing the hotel; the team had plenty of references, but it took drawing it at a bigger scale to detail what the hotel was going to look like on-camera. My sketch turned into a model, and that’s what we shot for the movie.

When you begin a new project, do you read every script end-to-end? What’s your process?

I always read the whole script first without bothering to take notes. Then I read it again & take notes. Over the course of a project, I'll read it to five times or more. The script is the basic thing; you have to have something on paper, then I end up coloring it in. I've been on projects with wonderful scripts; and I've been on projects with not-so-wonderful scripts: You can make a good movie bad script, but you can also make a bad movie from a marvelous script…

Given your role, how does the research phase differ for each project?

There are contemporary things; they're all around you, and you just have to keep your eyes open. The projects that stand out for me are always the ones where I have to do a lot of research—a period piece, conjuring up something science-fiction... It's gotten so much easier, though; it used to be all books, magazines, and trips to the library. Now, you just go online and there's an overwhelming fire hose of information.

Production Design is like conjuring worlds from nothing. How did you get into it?

I always bring it back to my family & my exposure our marionette theater; I was about eight-years-old when it came into my life. It's a classically fashioned Eastern European family theater with these little puppets… it's basically a theatrical dollhouse. I did a lot of shows that way [growing up]. I went on to do some acting in high school, then more in college; then I began directing and film work. The funny thing was, when I was directing shows at Harvard it was hard to find a student who was any good with a hammer! I ended up having to build a lot of my own sets, and actually I found it was the most enjoyable part. You're dealing with the world of things and telling a story that way.

Does fantasy play into our reality more than we think?

If it's a story worth telling, there has to be some kind of imaginary aspect. I love the magic, the surrealism, the symbolism of fantasy. Life is more than a photorealistic soap opera.

What’s the importance of storyboarding an idea for a film? How does this play into your role?

I’ve done a little bit of storyboarding, but I don't typically. It's a weird speciality… first of all, it’s time consuming. If I'm designing or art directing a project, I’m usually too busy to spend time going through the process of “boarding out” concepts. I work with storyboards to try and make them into realities that we can photograph.

There are people who are fantastic, very slick, at this kind of stuff; then there are people that don't really draw. When they do their own storyboards, that can be hysterical: Bruce Beresford comes to mind; he did these marvelous little stick-figure drawings; they're hilariously childish, but they tell you everything you need to know.

Wes also does a lot of storyboarding; he even creates these animatic projects where he’ll take his favorite storyboard artists’ boards, and string them together in a shortened version of the movie that he narrates. They’re genius.

What are your favorite mediums to work with?

I like a pencil—I choose a Mirado Black Warrior #2. I also have my drafting tools, acrylic paints, and so forth. I find watercolor more forgiving: If you have a good drawing then you're halfway there. Watercolor goes a long way towards suggesting an idea. I keep my toolkit extremely basic because I'm frequently traveling for work.

Can you tell me about the importance of color in film?

Here’s a funny thing: All the work that I've done for Wes has been in black-and-white! He reserves the prerogative of deciding on final colors for himself. Sometimes he’ll do something whacko, like all the pinks and purples in Grand Budapest, which turned out to be genius. Ninety percent of the time, I’m in charge of colors: paint colors for the walls, the wallpaper, colors of signage that appears on camera, the cars. Decisions can come down to the tiniest details like variations of palettes, spectrums, vividness, saturation, you name it…

One thing to note is that your line of work isn’t just “drawing for the sake of it.”

I'll do sketches & I'll make pretty pictures—but the fact of the matter is that most of my job is translating those drawings into something that can be handed to carpenters to build & decorate. In those drawings, we’re including details like its size, which materials we’ll use to build it, how it moves around, where it sits in the studio... I’m really the person that comes up with construction drawings for these productions.

What's one set where you walked on and you just felt immediately a part of that environment?

I keep going back to Grand Budapest, but it was such a great experience. We were shooting in an old department store built in 1911. You can see the building with its six-story atrium and its unbelievable stained-glass window in the movie. Our production team offices were in the same building—so I would go to the “office,” which was also the lobby set of the Grand Budapest, and walk up to the sixth floor where we had our spot in the attic next to the stained glass skylight. You really had a sense of being there…

So you walked into the lobby of the Grand Budapest Hotel on your way to work?

Exactly. I would check-in with all the carpenters and painters to see what progress they had made, and see how things were coming along. It was a really nice overlap. Really gratifying.

How can the general audience learn to look at movies like you do?

This my problem watching movies: I see something spectacular on-screen—like in a Hallmark Holiday movie, where they’ve done-up the ballroom, rented the whole space, filled it up with flowers, trees, extras, and table decorations—and [in the script] it's just a quarter of a page. In the final cut, it's on-screen for maybe five seconds. I look at that & feel exhausted. Or it could be an intimate with two people in bed whispering sweet nothings. On-screen, it's super intimate and quiet; but right outside the frame there are a hundred people all standing around! I'm always acutely aware of what’s beyond the frame... so don't watch movies the way that I do! [Laughs]