Inside the Studio: Documentary Filmmaker AJ Oscarson on Capturing The Moment

Samuel Taggart

10 Minutes

AJ Oscarson strives to capture the truth of the moment. Whether crafting commercial work for the NFL, NBA, MLB, covering live events, or recording reality in documentary format, Oscarson's background in photography, journalism, anthropology, and film guides his every move. When Oscarson steps behind the lens, he takes with him an honest perspective, a sensitivity to culture and character, a keen sense of framing, and the ability to tell authentic stories.

His latest work proves the point. Produced by Fresh Tape Media, edited on Suite, and now available to watch on HBO Max, A Clean Sheet: Gabe Landeskog, is a six-part documentary series following the recovery of the eponymous Colorado Avalanche captain. Putting Landeskog’s emotional and mental journey at the forefront of the series, it isn’t your standard “hit the gym and get back out there” documentary. It’s a human portrait.

In this conversation, you’ll learn about how the Emmy-nominated documentary went from initial idea to final release after three years of filming. You’ll also learn how Oscarson’s varied background and nearly 20 years in the media industry have shaped his approach to every project, from making a subject feel comfortable in front the camera to ensuring you get the shot when the moment comes. Keep reading to go Inside the Studio with AJ Oscarson…

What’s brewing at Fresh Tape Media right now?

We're working on a bunch of different commercial projects, including some big work with Microsoft, creating commercials for their AI department. On the original content side, we're just trying to figure out what comes next. We really enjoyed working on A Clean Sheet. Now, it's about doing our homework and picking the next one.

Let’s dive right into some backstory on the docu-series, A Clean Sheet: Gabe Landeskog...

It actually started rather simply. He posted a photo on Instagram just after his knee surgery. One of our producers here, Avalon Koenig, DM’d him saying something like, “Hey, we're pulling for you!” He wrote back, “If you ever want to tell the story, let me know!” Fresh Tape had worked with the Colorado Avalanche over the past several years, so we weren’t completely unknown to him. We did a test shoot to figure out the pitch, and we just went with it.

The project took over three years to complete. What were the biggest challenges you faced?

I’m a huge believer in transcripts. You're cutting them constantly. Every day, you're taking notes—here's what happened, here's what could be interesting, here's what didn’t work. Over those three years, we ended up with maybe 2,000 pages of transcripts. After shooting, it just turns over to your system of highlighting key moments.

But over that long span of time, it’s really easy to get beat down. It's incredibly exhausting and it can be really confusing. You get lost in it—it just turns into words and pictures. Stuff that you think happened in December actually happened in October; you're looking in the wrong spot; all that kind of stuff. To avoid all that, to stay energized, you gotta love the process. If you're in it for the destination, you’re really gonna struggle. You gotta love that journey.

What are some of your tricks to make someone comfortable in front of the camera?

One of my first projects out of Grad School was filming intravenous drug users around Denver who scrapped metal. Everything they did, all day, was basically a felony. Very difficult subject matter. I would go hang out with them and just bring the camera. This is what it looks like, this is what it feels like to have it rolling. In an odd way, it was similar with Gabe [Landeskog]. I would just follow him around, shooting everything, making him feel comfortable.

To capture the right moments, a lot comes down to just being really mindful of where you put yourself physically in the space. You have to find the little patterns like how someone moves. If you're standing in the way, there’s a tacit reminder to them that you’re filming, and that might change how they behave for the camera.

It was a pretty run-and-gun production. What’s the strength of having limits to your work?

When I was completing my Master's Degree, we watched a documentary called The Five Obstructions by Lars Van Trier… his premise was to make a film with various, very specific obstructions. For example, one obstruction was making a cut every 12 frames. The point of viewing that film was to experience the premise of it: If you really understand how fertile the film medium can be, you can use every constraint to your advantage.

My take on that, in relation to the Landeskog doc, was that we had a small production budget. I used a handheld Sony with a microphone on it. Gabe would sometimes wear a lavalier [microphone] when we had time. But there was no easy rig. We didn’t want him to see that. It all had to be very clean because we were in his home, around his kids, and we wanted to reduce that production effect, try to normalize putting himself on camera.

That ended up being very beneficial. I just held a camera in front of my body on a knapsack—and that was it. There was no audio team, no big shotgun mic. You hear how people make documentaries, shooting with two or three massive cameras… we just got rid of all that. The story became more personabe and it really shows in the final product.

Talk about the editing process for A Clean Sheet. How did you stitch it together?

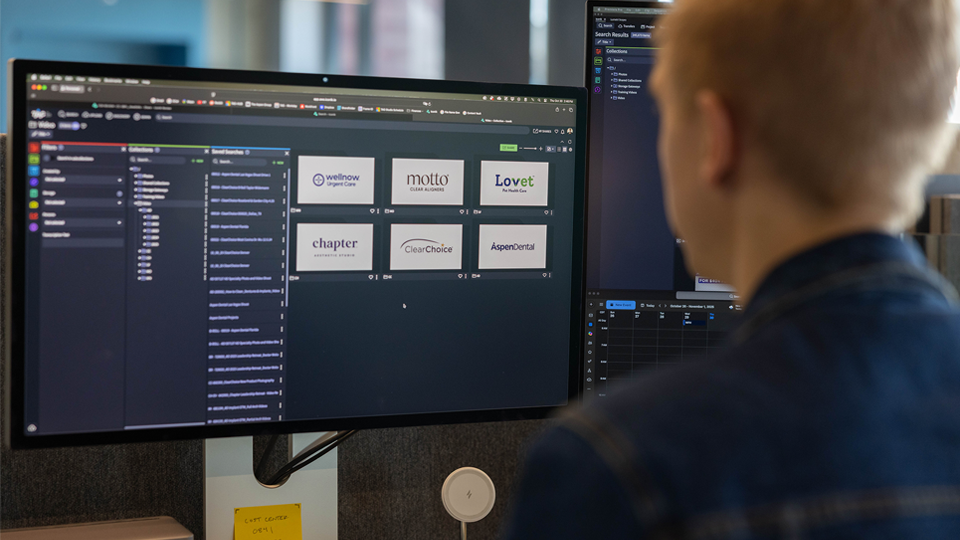

We had a different Adobe Premiere Pro project for each episode. I would be writing and editing episode three, while someone was starting to cut and pull shots for assembly on episode four, all while someone was finishing episode two. There weren’t rounds of reviews, though. It’s typically four weeks for an episode of television to get cut—we had to write and edit every episode in about nine days. So it was super fast, there was very little back-and-forth. It was just decide, decide, decide. Suite was honestly really helpful because we have some really talented graphics folks in Chicago and New York who are part of our network. We had editors who could easily pop in to the work.

Explain how your background in photography, journalism, anthropology, and film influence your work.

For my Master's in Anthropology, I had a great professor at UC Denver who was on the cutting-edge of sociocultural anthropology. I didn’t know what what I wanted to write my thesis about, I just wanted to help people, or advocate for something in some way. He put it very bluntly—I shouldn’t write a thesis, I should film it.

I left that meeting, went to Best Buy, bought a tiny camcorder, and just ran with it. I already had a photography background and the film side just clicked. Anthropology is very in the weeds about how to interact with people; the journalism side of it is joining a population, reporting on it, without altering it. The hard part is consciously putting a person or a group of people on camera to represent their sociocultural existence, and to do it fairly.

Every video you've ever seen has an edit to it. Even video content that doesn’t have technical edits, there’s still a decision about where it starts and where it ends. A lot of decisive (even divisive) things can happen because of those different decisions. Another component is the interviews. How do you conduct interviews? Where do you put the camera? How do you make folks feel comfortable? You can't just put a camera in a room and expect everyone to behave the same way. So, how do you get folks comfortable? How do you let them be themselves?

The journalism part is capturing it fairly, the anthropology part is understanding what folks might be going through while documenting it. You’re taking an immense world, and you have to put a 16x9 border on it. Wherever you point the camera says so much. You're dictating so much about someone else's world. You have to consider the visual anthropology, the ethical and moral implications of your shots. Being cognizant and trying to do it fairly as possible.

You're now the Head of Studio at Fresh Tape Media. How did you land in this role?

After I filmed that documentary short for my Master's thesis, I did solo operator work. I tried audio, I did PA, grip, I carried stuff around… I just begged to get on film sets. This probably resonates with a lot of people in the video and photo world—you just want to be there. That was 17 years ago at this point. I arrived at Fresh Tape four and a half years ago. It was a smaller company at the time, six or seven people. Now, we're at 20 or so...

Having experienced all those jobs as a generalist, my role at Fresh Tape combines them: I’m working on content, but also understanding the end-to-end pipeline of production. You need someone who can see that whole pipeline, to find inefficiencies, securities, all those types of things. And how it all comes together into a final product.

You’re based in Colorado. Why is Denver such a special hub for creativity?

Denver's interesting. There aren’t a lot of major cities around it, which offers pain points, but also opportunities. If you go to Los Angeles and New York City, people coming up tend to pick a role. They don't become generalists, but specialists. “I only touch cameras, I only touch electric,” sorta thing. Folks in Denver do everything because we don't have that kind of population working behind the scenes—and Denver is special for that reason.

Even just the physical location of Denver is special. I can get to New York in four hours, LA in two hours, Atlanta in three-ish hours, whatever it is. Being based here, you can easily get involved in a lot of different projects. You’re also seeing more projects pop up here because people are realizing that Denver is a city, but you’re close to desert shots, mountain shots, and of course you can get urban shots downtown. There are major sports teams. A big theater community. Good universities. There’s just a lot of opportunity to shoot myriad projects.

How does your photography background specifically influence your filmmaking?

When I wanted to get serious about filmmaking, I went out and bought a cheap Canon AE1 35-millimeter camera. Up until that point, I was shooting digital on a Canon 5D, or something like it. But I got into this habit—like a lot of us in this community—and defaulted to the “spray and pray”, where you're just shooting everything.

I bought that AE1 one to force myself to slow down. On a roll of film, you get 36 exposures (or 24), and that’s it. You have to be more curated. The documentary film world is that same thing—there are no takes. You're in this room, this thing's gonna happen, and it's gonna happen once. You've gotta pick your shots. That selective photo background really gives me confidence. Another component might be color… a lot of photographers do really interesting grades. They paint the way you feel about an image. In video it’s the same—you’re just doing that 24 times a second.

How does this minimalist approach help your video work stand out?

There's all these tools when shooting… depth of field, framing, lens choice. Each of them have an effect on what you want the viewer to focus on; as the filmmaker, you want to dictate what that is. There are many different styles—mine just happens to be minimalist. I've just always wanted clean lines, clean things, less distraction. Done well, it can make a really bold statement—and if you’re going to make something, make it bold. If you’re going to say something, don’t whisper it, say it loud. If you talk about scrolling through feeds, there’s so much content that’s aggressively fast, it has almost become our default setting. Leveraging minimalism can really help pieces stand out.