Inside the Studio: VFX artist Matt Hartle on crafting the visual identity of Hollywood's biggest blockbuster films

Samuel Taggart

10 Minutes

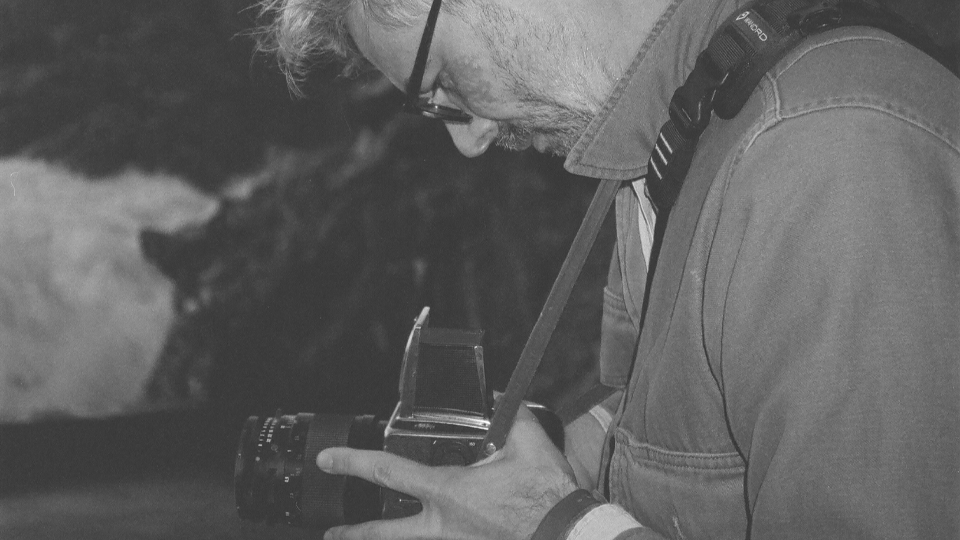

Featured Image courtesy of Matt Hartle/Deva Studios

Imagine this—you’re in the movie theater, the lights dim, and the latest installment of the Harry Potter franchise starts playing on the big screen. The opening scene sets the stage, and then the iconic theme music begins to play through the speakers. Through the clouds, words manifest—the title card, a visual moniker—appears on the screen. The first sequence is complete, and now the movie has really begun…

For Matt Hartle, partner & executive creative director at Baked Studios (NY, CA), these are the moments on which he’s built his career. From eye-catching movie trailers to stage-setting title cards, Hartle is one of the film & television industry’s go-to artists for opening sequences, motion design, and visual effects (VFX). Blending a classical art background with expertise of the most cutting-edge digital design tools and an inherent love of storytelling, Hartle’s work helps some of the biggest titles, shows, and production companies in the industry establish their visual identity.

Quietly, Hartle’s artistry pervades modern film. His extensive portfolio includes title card graphics for Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Superman, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, The Last Airbender, Watchmen, Pan, Troy, Hercules, and many more, as well as branded work & logo updates for Lionsgate, MGM, and Paramount. Overall, Hartle lets his work speak for itself, always matching the assignment with an eye-popping, fine-tuned final graphic.

Recently, the Suite Studios team caught up with the Montana-based motion designer, VFX artist, creative director, and writer to learn about his experience in the media industry over the last two decades. Hartle’s artistic focus is widespread but remains constant. From early inspirations in drawing and Renaissance painting to authoring best-selling sci-fi novels, and even a few words of advice for aspiring digital artists & creatives, keep reading to hear the latest from one of the film & television industry’s most prolific, unsuspecting figures right here on The Render.

To watch Hartle's full portfolio highlight reel, click here. Don't miss it!

What’s on your desk this week?

At Baked Studios, we’re working on a major film. There are hundreds of shots, and we’re utilizing footage from half a dozen cameras, each in different formats. We have shots from anamorphic lenses, spherical ones, consumer digital cameras, drones—everything from Arri to Nikon. They all have different color science, file formats, and workflows. This project is unique because the director fully embraces it all as part of the visual storytelling. Additionally, I’m working on redesigning a studio logo, and we’re working on a couple of commercials—lots in the hopper!

Incredible, so many moving parts…

Absolutely. At Baked, we tackle a variety of projects, from fluid morphs that involve creating new shots from several different takes, to set extensions, character animation, beauty work, fluid and fire effects, and much more. Our team is diverse and really talented. Most of us have been together for years, which fosters synergy, allows us to move fast, stay adaptable, and maybe most importantly — have fun while doing it!

How did you get started in the arts and eventually motion graphics?

I have always been interested in the arts. I was a terrible student with interesting notebooks; the margins were filled with drawings. In my teenage years, I started doing life drawing classes at our local college in Kalispell, Montana. That led me to oil painting; then, I had the opportunity to do a few art history tours in Europe. I went to Italy and got immersed in all of it. That was my inspiration growing up—my whole background was traditional. But I also always loved computers. At my house growing up, we had one of the first Macintosh computers and other Apple computers over time, and I was always exploring. In high school, I actually had a business doing computer graphics called Magical Arts; I would call clients during my study hall, trying to make a business out of this passion of mine.

Do you draw connections between your traditional education & the newer digital arts?

I believe there are similar disciplines that utilize different tools. Understanding color theory, for instance, applies whether you’re using a brush or a mouse. Artists have always had a desire and need to understand the tools and processes of their art. Another example: when Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel, he was the one grinding the pigments, preparing the surfaces, figuring out the compounds for the plasters, and drawing the cartoons. There are many parallels there to what we do today. Ultimately, it’s about creating a final image, but you must understand the technology and have a concept and aesthetic to carry out the work.

Back when I was in college, Industrial Light & Magic had an internal team called the Rebel Unit, which was doing a bunch of work on the Star Wars movies. On that team, individual artists were handling entire shots—one person would complete the majority of work for a given shot—instead of focusing on just one task and then passing it along to the next person in the pipeline. This was paving the way for individual artists to have more of a fingerprint on the entire scene—where people were finding roles as generalists.

When did you start focusing on movie trailers & title cards?

When I was in my fifth term studying illustration at ArtCenter College of Art & Design in Pasadena, I had a friend who was working on internal studio development for the first Harry Potter film. This was before it became the phenomenon it is today—essentially, internally, people at Warner Brothers weren’t sure what the property was, and the producer, David Heyman, needed to get everyone at the studio excited about the project. We were creating development pieces to help the Warner Brothers team better understand the story and the extraordinary impact the books were having around the world.

Later, I was teaching at Gnomon and the industry was changing rapidly. Toy Story had been released, and it seemed clear that hand-drawn animation would soon be disappearing—it required all these classically trained, incredibly skilled, and experienced animators to be retrained. The unions were sending them to Gnomon; it was a wild time because I was only about 20 years old and had people like the lead animator for Mulan in my class. After that, I worked at a studio called BLT in Hollywood for a little over eight years. BLT was the established movie poster/one-sheet powerhouse in Hollywood. They were expanding into A/V work, and I co-ran the motion graphics department with my good friend Alen Petkovic. My focus shifted to movie trailers and title sequences.

What's the secret to a captivating title sequence?

The graphics in a trailer really help establish the aesthetic for the property. Often, a film may not even have a visual identity from a marketing perspective. It could be very early in the process, and nothing has been shot yet. So, you come up with scripted ideas, begin working on title design, and undergo a thorough exploration to determine the look. Sometimes, you start with a screenplay or a rough cut of the film, and the team will request that you develop an aesthetic that complements those elements while avoiding clichés. There are numerous terms in the industry that you want to shy away from, like if you’re doing a fantasy film, they typically don’t want “swords and sandals,” or if you’re doing something Disney-esque, they don’t want “magically delicious”. You are consistently challenged to find a fresh approach to visually enhance and illustrate the story.

One interesting caveat is that the productions tend to operate independently from the marketing teams—which is nuts—they’ll often double-spend on title design. There are some exceptions: while I was working at Deva Studios in Santa Monica on Percy Jackson, the studio ended up using the same title from the trailer for the film, which was, of course, thrilling! Working with a great writer/ director like Christopher Columbus was a huge privilege.

However, working Troy when I was at BLT, I created the title for the trailer, and it was a big deal. I traveled to the production in Cabo with a photographer to shoot the set and recreate the wall of Troy. The typography for the title was based on Trajan; it was center-beveled and looked very solid and masculine. Then, for the film, they chose something different—they went with a thin, almost handwritten font. It shows how disconnected the two sides can be. It’s strange how filmmakers have can so much input, yet don't always seem to be involved in the advertising.

Primarily, you’re searching for something that complements the property. This might involve creating a design that seamlessly integrates into the footage, where it becomes part of the scene; or perhaps there’s a moment that fades to black, and then you introduce a card before returning to the scene; or it may serve to provide a visual impact that enhances everything. The latter is the most enjoyable because it allows for true creativity—envisioning a world where these elements coalesce. Ultimately, however, it should harmonize with the story and visuals.

As a visual artist, what initially led you into writing screenplays & books?

I always wanted to be a director because I love every part of the process, creatively, of making a film. I had a friend—one of the producers for James Cameron who worked on Titanic—and we talked about the importance of storytelling. So, I began writing screenplays. I wrote many and also made a few short films, and I really enjoyed the process. I wore every hat, from shooting to directing, editing, VFX, color, and sound design. It’s a wonderful and exhausting endeavor.

The problem with writing a screenplay, though, is that until you actually go out and make the movie, all you've really done is develop a blueprint. If you're a director, you don't want the writer to be directing on the page; if you're an actor, you don't want the writer telling you how to deliver the line; and if you’re a designer, you don’t want anyone telling you what the set should look like. Writing a screenplay, you need to describe the story, but nothing beyond that. In the end, as a visual person, the screenplay was the speed bump to making the pictures.

So, I made some short films, won awards, and enjoyed it, but I found it challenging to roll it to the next step. So, I thought I'd try writing stories, writing books. It turned out to be the most complementary creative process for me. In writing a novel, you create the entire world; you’re not just outlining it. I’ve just completed my fourth novel, and I’m more fascinated by the writing process than ever. It’s literally the thing that gets me out of bed at 5AM every day. When you find something you love that much, it’s such a gift, and you have to grasp it with both hands.

How do you find all of your different artistic endeavors mingle in your work?

For me, they are different sides of the same thing. The hardest part of any creative discipline is communicating what you see in your mind with your audience. I find that it all flows together. Because I’m a visual person, when I write, I’m working to describe what I’m imagining with words. When I’m on the computer or in front of a canvas with a paintbrush or holding a camera, I’m working to manipulate the tools to communicate the concept or idea. Obviously, the disciplines are very different, but it feels as though they are pulling from the same creative well.

What advice would you give to other artists who want to intertwine their inspirations?

Just be open to inspiration. It can come from anywhere—music, literature, movies, games, interactions with people, or travel. It’s essential to absorb as much of the world as you can. Many of the perceived limits you encounter as a creative person or as an individual for that matter, are in your mind. We all face barriers like, “Geez, if I just had a million dollars, I could…” But that’s not really where setbacks occur—believing you need a million dollars to create is the hurdle you must overcome. Great things are possible with limited resources. That’s what’s so exciting about the democratization of technology. Information is everywhere, so there’s nothing stopping anyone from creating. There’s no barrier between you and the act of creating something to share with an audience. Get out there!

One other thing I would encourage is that people should definitely go to school. When I went to Art Center, being around others who were as passionate about this stuff as I was, the friendships, relationships, and exposure to different ways of thinking were so formative. That stuff is not likely to come through a computer or YouTube videos. You have to place yourself in that position. There’s nothing wrong with learning online—I do it all the time. But you have to get out there and expose yourself to the world and let the world in, and school is a great first step. You want to be training yourself to learn so that you can have an exciting job twenty years into your career.

What do you see happening next in the world of digital VFX?

The decentralization of post-production in filmmaking is a hugely positive thing. Having access to remote workflows gives you access to a whole world of talent. And its reciprocal, it also gives those freelancers an opportunity to access new projects. That’s huge. It's really going to empower productions to find new ways of making movies. Of course, AI represents a major shift—we don’t yet know where that’s headed.

Any parting thoughts for The Render's creative audience?

It might be a little non sequitur, but I would say: If you’re a creative waiting for inspiration, stop waiting; you just have to go do it. If you want to be a writer, just write. It’s so succinct, but it conveys powerful knowledge. If people want to make films, then go and make them. If you wish to do visual effects, just do it. There’s very little stopping you, especially considering all the barriers that used to exist regarding technology.

Growing up, when I wanted to do stop-motion animation, it was all VHS, and I didn’t have a camera… I borrowed one from my grade school. Full start-stop-play buttons, all that. Now, you can use your iPhone; it shoots in 4K, and you can edit and set it to music—all in the palm of your hand.

There are no barriers between you and creativity. Lastly, always view all your work as a sketchbook. No single project is your masterpiece, your Sistine ceiling. It’s all just pages in a sketchbook, and on some level, it’s about the numbers.