Finding The Essence of Filmmaking: Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC

David Heuring

10 Minutes

Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC discusses vital moments on projects both sprawling and intimate...

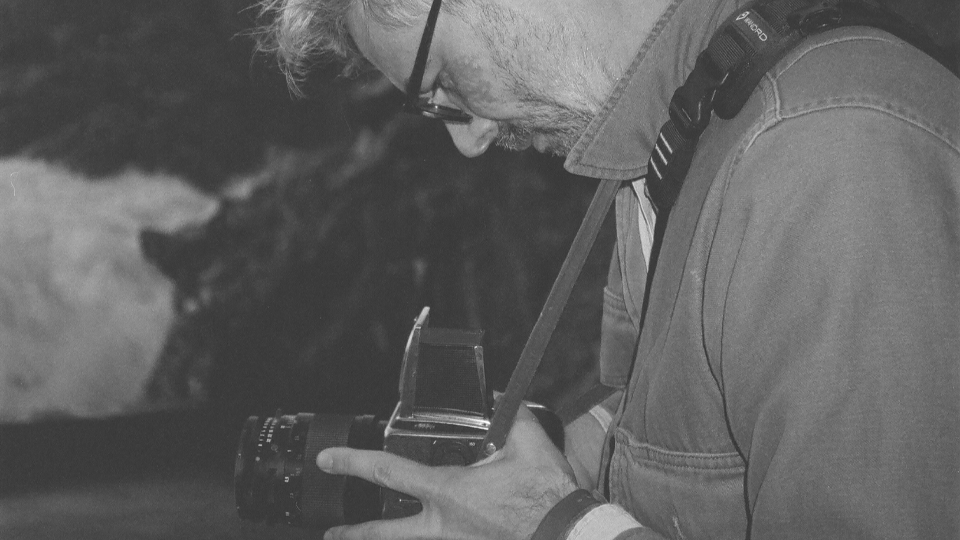

Director of Photography Phedon Papamichael has forged an unusual path in filmmaking. His father was a well-known raconteur and production designer in Europe who worked with John Cassavetes. The younger Papamichael was born in Athens, educated in Munich, and came to the U.S. before he was 21. As a young man, seeing Le Mépris (Contempt), directed by Jean-Luc Godard and shot by Raoul Coutard, was a turning point. “I was fascinated by that film, the way the camera moved and all the wide shots,” he says. “It was very graphic. It actually resembled my still photography work, because I had a similar sort of style, with graphic primary color surfaces and shadows and textures, with symmetry and long lateral camera moves. It was the first time I wrote down a cinematographer’s name.”

Later, using a 16mm camera borrowed from family friends, Papamichael photographed a film that won the cinematography prize at the Cork Film Festival. Soon he was shooting low-budget schlock for Roger Corman, where his crews included future masters like Janusz Kaminski, Wally Pfister and Mauro Fiore. Since then, he has balanced more intimate work with bigger studio projects, forging relationships with visionary directors like Alexander Payne (The Descendants) and James Mangold (3:10 to Yuma, Walk the Line).

Eventually his career led to Oscar nominations (Nebraska, The Trial of the Chicago 7) and some of the most complex and technical filmmaking projects ever undertaken–most recently, Indiana Jones & the Dial of Destiny. Along the way, Papamichael has always interspersed smaller-scale projects, balancing the blockbusters with hands-on, human-scale fare like the recent feature film Light Falls, which he directed and co-produced.

“Working on a project like Light Falls keeps you in touch with the essence of filmmaking,” he says. “Of course it’s a very different experience from a film like Indiana Jones, which cost hundreds of times more. But when you get down to the heart of it, it’s telling stories visually with actors. The tools and techniques change, but when you’re searching for the right shot, your instincts and experience apply across the board. What you learn on the big jobs can apply to the small ones, and vice versa."

“The technical aspects of filmmaking were never a challenge for me–you can learn that by reading and by doing it,” he says. “I don’t consider myself a technical person. I barely know where the ‘on’ switch is on the camera! The non-technical aspects are what make you a good filmmaker—you still have to know where to put the camera, how to move the camera, how to light, how to tell a story. I see what I see and I judge it, and I know my tools well enough to achieve the results I need, and if there is something I don’t know and I need to know it, I learn it specifically for that picture.”

Accordingly, Papamichael keeps his toolset consistent. His standard camera setup, used on his previous five features, includes ARRI Alexa LF and LF Mini cameras, with Panavision T and C Series lenses adapted to the larger sensor and slightly detuned to his taste. On Light Falls, he went with a single Alexa Mini and uncoated Super Speed lenses. Adapting to a variety of budgets and subject matter has benefits, he says. Consider the images that come to mind with these titles: Million Dollar Hotel (Wim Wenders); Cool Runnings (Jon Turteltaub); The Huntsman: Winter’s War (Cedric Nicolas-Troyan); Ford v Ferrari (James Mangold); Nebraska and Sideways (both Alexander Payne).

“I embrace shifting gears and adjusting my palette,” says Papamichael. “But I always try to maintain a logic to the lighting, with natural inspiration, but heightened. On Indiana Jones, I enjoyed embracing more stylized imagery. The earlier films are not similar at all to my typical approach, but it was fun to dip into that world and stretch out.”

Light Falls is a genre picture, a thriller in which a young lesbian couple vacationing in Greece explore an abandoned hotel, and are taken hostage by immigrant Albanian laborers. Social-political aspects simmer beneath the surface. Papamichael spearheaded the project in the throes of the Covid shutdown, mounting a very small and focused production, mostly accomplished at a decaying Greek resort hotel on a remote stretch of beach near Athens.

One particular moment during the shoot illustrates the differences–and similarities–between large scale, high tech filmmaking, and the more personal approach required on Light Falls. Papamichael says that compared to technically ambitious and complicated projects, directing the relatively tiny shoot felt liberating.

“You’re free to react, without upsetting all the other departments and messing up months of planning,” he says. “The freedom to be light on our feet and take advantage is really wonderful and refreshing for everyone who works on massive productions. Sometimes I would step out for a break and see some stunning cloud formations, and we could pick up the camera and capture that and continue the scene later without any down side. Small-scale filmmaking has amazing advantages. Depending on the story, great films can be made with simple means."

“It gets down to the essence of what filmmaking is,” he says. “That’s the beauty of what we do, telling a story visually, finding these little gems that the actors give us. You can’t make Indiana Jones with a handful people. But ultimately, we’re trying to block out all the extraneous distractions and focus on the movie.”

Lessons from essential filmmaking like Light Falls can translate to the grand-scale big-budget visual effects blockbusters, too. Papamichael recalls his thought process during some key moments from the extended rock ‘em-sock ‘em opening sequence of Indiana Jones & the Dial of Destiny, where Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones swashbuckles his way through the Alps on the top of a hurtling train.

The sequence updates the cliffhanging thrills of the old Saturday serials–part of George Lucas’s original concept forty years ago–using the latest high tech tools and techniques. Papamichael and the crew traveled for five hours to the bridge location in Austria to shoot. Visual effects required reference cameras and the full array of on-set wizardry, adding mountain peaks and passing scenery. Post at Company 3 included additional vignetting and grain, which was shot against gray and layered on the image, as opposed to being done with a digital tool like LiveGrain. To some subtle degree, where appropriate, Papamichael and colorist Skip Kimball used digital intermediate techniques to emulate the more blocked-up blacks and shadows of Douglas Slocombe’s work on the original, which was done on film emulsion. Months of editing were required to assemble the various pieces in a seamless sequence.

Once Indy escapes the dangers, he turns to the camera and dons his trademark fedora with a heroic flourish. A seemingly random flash of orange-red light crosses him, a visual cue bringing fans back four decades to the now-iconic look of the original Raiders of the Lost Ark. The moment, the first of many classic beats and call-backs in the film, elicited a round of applause at a cast & crew screening at the Chinese Theater in Hollywood.

“Mangold has this great ability to tune the audience in on the characters and the performances and the humor, even in the middle of the action,” says Papamichael. “As a result, the action becomes much stronger. Great action shots become special when you have the moments with the characters, and you play the little intimate beats. Those moments are Mangold’s trademark, and he’s very good at it–even Steven Spielberg acknowledged it. So in a way it came naturally to us, and we understood it well.”

And yet, it’s akin to certain key moments in Light Falls–storytelling opportunities seen and grasped by the filmmakers. In one scene, one of the Albanian kidnappers seems to unintentionally and wordlessly reveal his sympathy for the hostage. To make the screen work narratively, Papamichael needed human skills rather than technical prowess–the idea, a rapport with his actors and crew, and an understanding of the human face.

“No matter how big or small the movie is, those little things are crucial,” says Papamichael. “The tilt of his head has to be just right, and how are we going to come around with the camera? What is the right moment? It’s a dance. Regardless of how many trucks we have and how big our basecamp is, it’s our job to find and weave in these little gems that the actors give us. Harrison Ford is of course a skilled professional, and it’s such a pleasure to work with him. Our cast on Light Falls was mostly amateurs and beginners, but in either case, you’re trying to create and underscore these expressive moments.

“The way I see cinematography, and filmmaking in general, is related to how I see life,” says Papamichael. “If you don’t have a point of view, you probably won’t have much of interest to say. The way you see things in an accumulation of everything you’ve experienced in life. What the camera captures, and the emotional effect on the audience, is the result of all our conversation, arguments, laughter and tears over the years. And that human aspect is what makes filmmaking such a satisfying undertaking for me.”

Papamichael is currently shooting A Complete Unknown with Mangold and actors Timothée Chalamet, Elle Fanning and Edward Norton. The film depicts Bob Dylan’s controversial switch to electric at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival. This time out, he is shooting on the Sony Venice 2 combined with custom-made Panavision lenses, hybrid versions of their B and T Series anamorphic lines that offer excellent close focus and minimal bending.

A Complete Unknown is expected in theaters in early 2025.